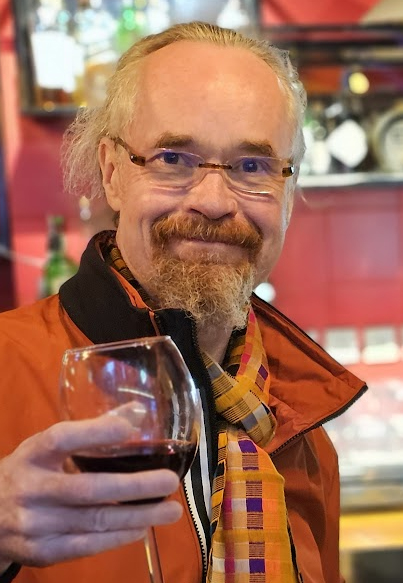

Mike Atkin stopped painting people when architecture started calling. Here, the Director of HEAD Architecture in Hong Kong shares some surprising insights into this most storied of cities as it enters the Year of the Dragon.

The Hong Kong of 2024 is very different from when I arrived in 1996 – just before the handover in ’97. As loads of people were leaving, I was part of a group of 12 architecture graduates who decided to head over from Glasgow School of Art. There are still five of us here, nearly 28 years later.

I didn’t set out to be an architect. I studied history of art at Manchester University. Then I found myself in Barcelona making paintings of people and buildings. One day I just stopped painting people and it was all about buildings. Which led to six years of studying architecture in Glasgow.

My first architectural job in Hong Kong was brilliant. I worked alongside a guy called Mark Panckhurst, and we completed some great-looking projects together. So we made the leap and set up on our own. The company needed a name – but not the usual boring acronym of our initials. HEAD was inspired by a visit to the temples in Siem Reap, Cambodia. Those giant stone sculptures spoke to us.

Hong Kong is a vertical city where space is at a premium and property can be ferociously expensive. The higher up you go, the more expensive. Because in theory it gets a bit cooler in this hot, humid city – there’s a bit more air up there. When you get to the Peak [Victoria Peak, in the west of Hong Kong Island], that’s where the most exclusive properties are.

Harbour view from Victoria Peak, Hong Kong, where the air is cooler and prime property is a magnet for investors. (Photo: Shutterstock)

When visitors think of HK, they’re usually thinking of Hong Kong Island, with all its skyscrapers. But we’re surrounded by over 250 islands. The bigger ones, like Lamma and Lantau, are full of expat communities. These islands are slowly growing in population, but still some stunningly beautiful backwaters exist – you can commute by boat and read a book on your way home from work. It’s a special side of Hong Kong people don’t often see.

Something particular to this part of the world is what we call a “village house”. Historically, the eldest son in a family has a constitutional right to build a three-story house on a ding plot in the village where they’re born. If that sounds rustic, it’s the job of modern architecture to help tradition express itself in modern ways.

The team at HEAD Architecture reimagined a typical village house on lush Lantau Island – a short boat journey away from Hong Kong Island. (Photo: Graham Uden)

One of our most satisfying residential projects at HEAD is called House 98. It was our take on the typical 700 x 700 x 700 square foot village house. Based on that standard pattern, we hollowed out the center to create a full-height void topped with glass. Getting it through regulations wasn’t easy, but the finished form is a beautiful thing.

House 98, aka the Village House, broke the rules of traditional cuboid three-story island structures by incorporating a glass roof and full-height central void. “People thought we were crazy, reducing the footprint of the house, but we created something beautiful,” says HEAD Architecture’s Mike Atkin. (Photo: Graham Uden)

Beyond designing beautiful spaces, we create entire brands. For two food retail clients, we do everything from store interiors to uniforms, delivery vans to photography. That’s how we work with Great Food Hall, which is like the Dean & DeLuca or Eataly of Hong Kong. I love projects that develop through fine-tuning and upgrading across locations.

HEAD Architecture’s design for Hong Kong supermarket Great Food Hall incorporates every aspect of the brand, from retail fittings to staff uniforms. (Photo: Graham Uden)

Mike Atkin enjoys working with brands whose identities evolve over time and locations, such as luxury whisky, wine and sake retailer Liquid Gold. (HEAD Architecture)

We are modernists. We are practical. We allow for extrovert touches but only when they’re justified. But not boring. I don’t do white walls anymore.

At home, I have orange walls and yellow walls. Green walls in the bedroom, otherwise I wouldn’t be able to get to sleep. Floor-to-ceiling paintings. Red furniture. It’s a home full of color and books and art and sculpture.

My wife and I now live in Ho Man Tin district just outside of Mong Kok in Kowloon. We get more space and great views. A very large living room and a beautiful kitchen. We’re the only people in the building with this layout. And probably the only ones with orange walls!

Mike Atkin’s love of the color orange extends to his home and his wardrobe. (Photo: Mike Atkin)

Mong Kok is the beating heart of HK’s culture. Especially the food! Some buildings have 50 restaurants in them. You know how in New York people aren’t shy to ask table neighbors what they’ve ordered? Same here. Or Barcelona, where sharing food is ingrained in the culture. That communal experience is deeply important here – dim sum and hot pot and street food – especially for Lunar New Year. It’s all about coming together.

Designs on Hong Kong? Ring in the Year of the Dragon by exploring some of the city’s most enviable locations with Forbes Global Properties.